Some Notes on Music, Religion, and Guenon's Solitary Voice

"Concerning non-vocal music, by which I mean one involving any use of pitched musical instruments, it is humbly and with all deference my opinion that all such activities should be abandoned in favour of purely vocal chants handed down through the oral tradition. It is more than likely that if a free reign of music was permitted in a society displaying even a slight state of decadence, there would remain very few musicians who display a true understanding of the traditional order and the purpose of music within it, which is a role purely subordinate to that of the traditional institutions; instead, as in the case of Europe, we might face ourselves with certain groups infiltrating the musical tradition and subverting it from within. Certainly, the historical record would bear this out. The events of the past few decades with the emergence of the most vile and repulsive 'composers' such as Erik Satie and Erwin Schulhoff offer the perfect example."

I'll take both, the vocal experimentation along with instruments approaching total noise.

https://youtu.be/9Yw4yfeOhv4

Guenon's great mistake, like that of most traditionalists, is to assume that a glimpse of the eternal is to be reflected in the laws of religion, in what endures. Yet, the mysteries of the Greco-Romans tell us something completely different, rites are more than anything a turning away, a ward against forms of judgment that we are not prepared for.

The Gorgon pediment threatens all who enter the temple: one may be petrified by what is to be found within. To endure is to go beyond one's dominion and be cursed there forever. Paradoxically, it is the moderns who are obsessed with the endurable, bringing their cities to ruin only to prove how they might stare back into Medusa's gaze in perpetuity. The German soldier sings of his death to his wife in the grey snow before Stalingrad - his own tactics now old to him, yet infinitely more barbaric.

Music holds power over us like shimmering light in the cairn. It arrests and releases, there is no need of violent control - its means are certain, incantation takes us between time.

The untrained voice and the violence of that which survives war. It is easy to forget that the voice and its instrument are one - the war story does not change, only the atmosphere necessary for the return of triumph over foreign lands. This is why antiwar music is the most violent in its structure, industrial shipping of a greater form of destruction. He sings a lament for those about to be conquered, relieving himself of a responsibility of which he is uncertain. The soldier laments his own crimes, stories in which he attempts to relay the feeling that even though he has returned he may never again see his home.

Great structures are a relinquishment unto time, this is why blood was poured into the cornerstones of ancient temples. One may imagine that the Caryatids disappeared along with the abandonment of this practise.

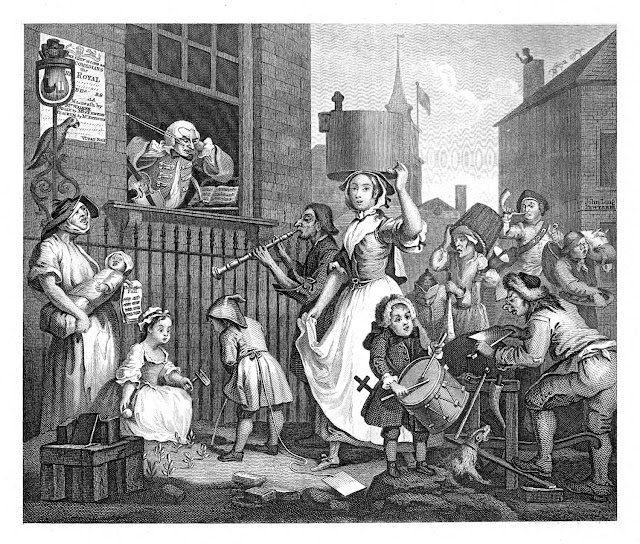

All wisdom ended with the rebuilding of the Temple of Athena, out of ruins man rebuilds his own figure as triumphant in the Gigantomachy. Humanism and the first appearance of modernity may have followed similar laws, abandonment of the oath made to troubadours. After this music became the art of servants. Theological luddism in the art of Bosch, much of the lost music held a similar quality.

One should be careful here not to directly transpose the laws of architecture to that of music, yet it is likely that general principles may be applied based upon similar philosophies of time. The irreal gives a sense of movement, the form which surrounds the figure as an eruption from within, yet his law of power is determined by forces outside of himself. In the realistic figure, being has been lost, one is paralyzed by his own abandonment in time. The Gorgon disappears, but has even greater effects on the observer.

Ancient music remains speculative due to the small number of surviving works. Yet, what we have suggests a similar mystery before time. The instrument and the voice accompany one another as swirling winds, discordant in form yet increasing the drive of the reveler towards merriment and abandon. Orff's music appears violent in comparison, yet it exists as antiquated rhythms within a world which can no longer resonate with deeper sounds; only the scientific advancement of sonic wave capture remains, where torturous shapes go to war with echoes. The Oceanids call to Prometheus emits a wondrous beauty in comparison, the cove where the receding sea betrays the hours we have to the next point.

It is hard to imagine the triumph of Parmenides in the realm of music, it has the life and death of Heraclitus in its rhythms. Yet the One remains in the most discordant. This is felt, perhaps more than anywhere, in the 1-3 beats of Swedish folk music. It is as if the song itself is being pulled into the unworldly, machinic elements approach us in silence. Here the eternal exists as a mill being worn down along with that which it grinds into fine powder; whirring sounds are predominant, and only disappear in the cities, in the recording studios.

As technique music can be divided into the forms of being, giving, having, and receiving. The fiddler writes for the dancers in fields, forests, and lonely homes. The sense of giving is predominant - he receives only in the 'Hups!' which accompany his transitions, switches into new songs, or great moments of skill which suggest his being as an instrument of the devil or god. The military quality may be noted, the same shout only on leave.

The fiddle differentiates itself from the violin through the right hand, the bow as opposed to mastery over the isolated strings. Air, pulse, and other natural instincts are transmitted through the body into the instrument. Where classical retains its performative qualities it approaches these elements.

The left-hand path of the violinist takes as much as it receives or gives. Classical is melancholy for the folk music of the north, it exists within the shadow of ancient ruins. The machinic quality strains as an equal and opposing force to those who appear as stone figures cut from the seats of the auditorium.

It is necessary to consider Nietzsche's comments on the vocal dominance in opera: the rationalisation of the idyllic. Perhaps we cannot surpass this, however, a possibility remains in clarifying the divided world of the voice and the instrument in music, its Cartesian quality. The operatic voice is a having, or even taking; its aesthetic exists in contradiction, a disgorgement of its own art into formalism. And yet it is perhaps the voice itself which marks the mastery of reception of eternal law and dominance over artistic creation.

Certainly Christian music remains the archetype here, a receiving completely opposed to Nietzsche's operatic voice. This is an uncertain territory between that which dominates in folk and classical, and it is much more difficult to perceive the voice as a reception compared to that which accompanies an instrument. One must consider the architecture in which this occurs, defensive structures in which heaven gives structure to the voice.

A simplicity beyond that of Heidegger's field path reveals itself. Even echoes from beneath ruins and arches can be heard. One may note the conflict within choral works and the attempt to relinquish one's own being. The Christian attempts to domesticate the monstrous through a strained form of kulning; the folk recognises the weakness of gods before greater forces. In the greatest myths human insight remains a danger beyond the world.

"Bronze is the mirror of the form; wine of the heart." In the Dialogue of Water and Wine death appears as a transitional phase between celebration and simple life. One must commend the Christians for their laws of enduring sound; refraction and curved stone which causes the eternal to reflect upon itself. The small flame may be transmitted into fire at a walking pace; the Christian seeks the denial of this physical law in his processions.

Similarly, the drone of the hurdy gurdy. There is no instrument more mechanical, the drum machine seems a relinquishment of technology from itself in comparison; the telluric quality of noise music. Otherwise, the subtleties of left- and right-wing industrial where the artist is little more than a means and technician. Endless wires and feedback loops, tubes in the smallest mechanisms attempt a release of sound into its own world. The artist seeks incantation before his instruments.

Only a true master may cause beauty to fall out of the monotony of a typewriter. The lament of mechanised music in contemporary art circles is only for its loss.

The Russian Soul seemed capable of transposing mechanised destruction through the beautiful instruments. The failure of socialism may be seen in the incapacity to unleash this musical power, just as the Western world had to abandon all culture in apologetics for its wars. Drumming as the ejection of magazines, the time scale of machine-guns and precision strikes. Perhaps the most striking example of eternal qualities in what passes instantly

Where Wagner threatens the performer with the destruction of his instrument or voice the amplified instrument is an inverse form of the operatic, often to the point of satire. This has become an element of heavy metal music: the human voice driven on by the immense power of noise. Hagen sings beyond death. Siegfried rises into the sky as lightning strikes. Even the most violent music is a falling away towards the horizon, the romanticists proved this more than any other. Death urges us onwards through all triumph.

Incredible lessons may be drawn from a comparison of vocal-dominant folk, classical, pop, and even extreme music, along with that of the choral, operatic, cantatas, and lyric poetry. The power of the voice over dominion may be felt, and one should be careful not to ascribe value beyond its appearance in its own time. What may be felt throughout all artistic eras is the conflict of being, one which gives us a sense of the struggle of man in his age and the forces of eternity that resound as echoes. For even the eternal is ever-changing, and our identification with a single season indicates that its spirit has been lost to us.

The Christian receives through his voice, the mystic power would not be achieved without this technique. An immense vulnerability on the part of the singer calls for God to sing through him, then the lamentation, the melancholy of the voice before the death of God. The choral works begin to fall away, approach folk in their style, similar to the folkish march of the waltzes where dance rather than performance remained as the central method.

Refined music died in its center, only its disparate qualities allowed it to endure. This highlights the uncertain territory between the eternal and the ephemeral. With its law of survival the modern period may have unveiled this paradox of material dominion more than any other, the greatest things we have are fleeting and only endure just above the surface of the earth, defying gravity and manipulating the senses. Folk music is at peace with this, the simple occasions within kitchens and barns. Regional anthems have survived while the great national anthems are long forgotten; the Christian voice takes on a nihilist quality.

The opposite of the rationalising voice can often be heard in the cantata, the voice driving forward and pulling the instruments into mechanised accompaniment. "Mortuus in anima, curam gero cutis." In this case, the soul buries itself in the flesh. There is no need of taking or receiving even where it may first appear as the law.

The opposite may also be true, machinic elements unleashing the Dionysian. What the rationalist is capable of destroying is one with the sorrow before mysteries.

"The merry face of spring turns to the world, sharp winter now flees, vanquished; bedecked in various colours Flora reigns, the harmony of the woods praises her in song. Ah!" Time disappears within its seasons, just as flowers rise from hell, and the essence of winter is felt within the last cold hollows of the woods where the sap remains frozen in its maple trees.

The form is also dependent on its substance; in his second spring man appears as a god. Music lives within a lost realm, the farmer's daughter infiltrates the royal stable and awaits a future that will save both families. Harmony arises within the spiritual war, by its very nature opposed to laws of duration.

Comments

Post a Comment